By Rieky Stuart and Stephen Brown

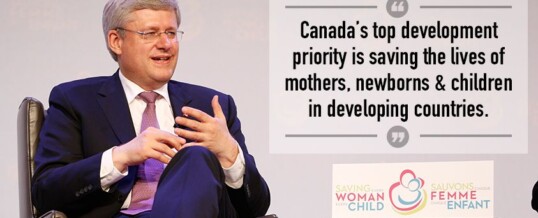

The Canadian government’s recent Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (MNCH) Summit in Toronto has not lacked for cheerleaders, especially NGOs receiving funding under the MNCH initiative. Prior to the summit, only a few critical voices were cited in the media (mainly from the McLeod Group) and most journalists, such as Paul Wells, initially set aside their cynicism and were won over by the cause. However, the government alienated many by excluding the media from most of the discussions, allegedly ‘to ensure frank discussions’, but more likely to prevent the reporting of criticism of Canadian government policy. In other words, to avoid frank discussions. Increasingly, the event looked like a vanity summit, seeking to show a kinder, gentler face of Conservatism and rally Canadians around its championing of a literal motherhood issue – while ensuring that the voices of those who had evidence-based criticisms of the Canadian approach would not be heard.

The billions of dollars promised at the summit are very welcome and will do great good. However, Canada could do much better. The importance of human rights and access to safe and legal abortion have already been discussed in blogs by the McLeod Group and Amnesty International, as well as a Globe and Mail editorial, among others. Here, we want to raise three other issues that have not received enough attention in public discussions of MNCH: contraception, sustainability and root causes.

First, contraception. The single best way to ‘save’ the lives of mothers and children is to increase the accessibility and availability of modern contraceptives. A trial in a rural area of Ghana found that when contraceptives were made available through local health clinics, deaths of children under five declined by almost 60%. In other words, the easiest way to save the lives of young children is to make modern contraceptives widely available at affordable prices and to help make their use socially acceptable. This approach has proven successful in countries as varied as Iran, Bangladesh and Rwanda.

And that is only one of the benefits. A widely accepted study determined that modern contraceptives avert 187 million unintended pregnancies per year (and an additional 16-20% if current demand were met). These averted pregnancies, in turn, prevent:

- 60 million unplanned births

- 105 million induced abortions

- 22 million spontaneous abortions

- 215,000 pregnancy-related deaths (79,000 from unsafe abortions)

- 2.7 million infant deaths

- 685,000 maternal deaths

This information leads one to question why the availability of family planning is not front and centre on Canada’s MNCH agenda, as it is in the US and the UK.

Second, sustainability. While international and local NGOs can provide maternal and child health services, what happens when the external funding runs out? The emphasis needs to be on delivering health care through national systems and strengthening those systems, not setting up special, time-bound initiatives that will fail when salaries can no longer be paid or supplies run out. It’s not only today’s babies and mothers that need ‘saving’ – it’s tomorrow’s too. This essential element of ‘local ownership’ is key to effective, sustainable development assistance (see also previous McLeod blog).

Third, root causes. The government’s approach to MNCH lacks an understanding of cause and effect, of symptom and cause. It’s like the story of well-intentioned people pulling babies out of the river and feeling they are doing a good thing, without finding out why the babies are falling into the river in the first place. That’s not to say that cause-and-effect relationships are simple. But the best evidence we have in this area comes from two recent World Bank reports: the World Development Report 2012 and Voice and Agency: Empowering Women and Girls for Shared Prosperity.These reports tell us that a key determining factor affecting health outcomes, including MNCH ones, is the degree to which women have a say in their lives and their communities. A CARE study in Bangladesh, for example, shows that programs that empower women were more than twice as effective at reducing stunting rates in children as comparable ones that didn’t. (See also previous blog.)

Instead of organizing narcissistic, self-serving summits, Canada would do better to follow more closely what the evidence tells us on MNCH. That would ensure the billions of dollars we are spending are put to the best use possible. In the end, that is far more important that feel-good messages and photo ops.