McLeod Blog by Rieky Stuart, October 12, 2017

During a panel discussion at the recent CCIC annual conference, Celina Caesar-Chavannes, Parliamentary Secretary to the Minister for International Development, mentioned the case of a Pakistani woman forced out of her home by her husband, separated from her children and left penniless (see our previous blog). She stated that “the system is broken” and used this example to highlight the problem of cultural norms and how they needed to change for foreign aid to be able to do any good.

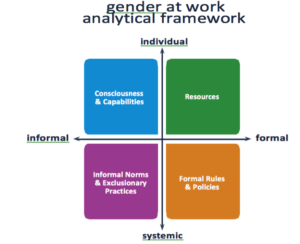

For years, development practitioners have tried to understand how change in favour of gender equality comes about, in order to better promote it. One useful framework for such change has been developed by Gender at Work, a global not-for-profit organization with associates in Asia, Africa, Europe and North America.

The following 2×2 matrix summarizes the framework:

Source: Gender at Work

The top two quadrants are clusters relating to individuals: on the right, changes in measurable individual conditions (resources, voice, freedom from violence, access to health) and, on the left, changes in individual consciousness (knowledge, skills, political consciousness and commitment to change toward equality). The bottom two quadrants are clusters relating to systems. The cluster on the right refers changes to formal institutional rules as laid down in constitutions, laws and policies. The cluster on the left represents changes at the informal norms and cultural practices that maintain inequality in everyday practices.

While change is needed in all four quadrants, work in each quadrant on its own is insufficient for sustainable change. It is important to analyze how efforts in one quadrant can support efforts in others.

For example, a study found that the decision to reserve 30% of positions for women in local government in India (lower-right quadrant) has resulted in increased resources going to women’s priorities (top right). Over time, the skill and confidence of women members increased and they were able to gain support and respect for their priorities (upper-left quadrant).

We know that a committed individual, such as Malala Yousafzai’s father, can influence not only his daughter’s future (upper-left quadrant), but persuade many other parents around the world to educate their daughters (lower-left quadrant). At the same time, increased emphasis on schooling through international development cooperation provided increased resources for girls to go to school (upper-right quadrant).

As a result of these efforts, several developing regions have achieved gender parity in primary education, while the gap has been significantly reduced in other regions. Paul Martin, while Canada’s Finance Minister, along with his British counterpart Gordon Brown, pushed for the World Bank to fund universal primary education (lower-right quadrant).

Providing women with marketable skills (the upper-right quadrant) has improved their own position in the family and the community, and encouraged other women to earn income. In Bangladesh, efforts by major NGOs such as BRAC to directly challenge social norms such as sexual harassment of schoolgirls (so-called “Eve-teasing”) and to create employment for poor women have contributed to a major change in social norms in recent decades (bottom-left quadrant). BRAC began by making micro-credit available to women (upper right quadrant) and found that also supporting efforts to change social norms amplified the results of their economic, health and education investments.

In Morocco, the women’s movement successfully collaborated with the government to win public support for a major change in family law (Moudawana) (lower-right quadrant) that gave both women and men equal rights and responsibilities for marriage, divorce and care of children. The cartoon below is one message in a brilliant communications campaign developed as one facet of the law reform, illustrating how women aged 18 and up can now get married without their guardian’s permission (bottom-left quadrant).

BEFORE AFTER

Source: Royaume du Maroc, Secrétariat d’État chargé de la Famille, de l’Enfance et des Personnes Handicapées, La Moudawana, autrement, 2006, p. 22

During implementation of the reform, the state insurance company agreed to support social safety net payments of child support when the parents had no means to do so after divorce (upper-right quadrant).

How to encourage change in social norms at the organizational and societal level – the problem raised by Caesar-Chavannes and illustrated by her anecdote of the Pakistani woman – remains the least explored and most challenging form of change. But we know that social norms can and do change: Our own lives and opportunities are different from those available to our parents and grandparents.

While we still have a lot to learn about how to support such change, there are many positive examples to draw on. Claiming that “the system is broken” and waiting for such change to happen before increasing Canada’s aid budget, as suggested by Caesar-Chavannes, is a self-defeating approach. Since the Canadian government is promising leadership, let it lead in this area by providing greater resources and innovative programming as part of its Feminist International Assistance Policy.

Rieky Stuart is an associate of Gender at Work. For an excellent primer on foreign aid’s role in changing attitudes on gender relations, the McLeod Group recommends a 2001 document prepared by CIDA, entitled “Questions about culture, gender equality and development cooperation”, which can be downloaded here.